Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

Interview with an organiser from the Quebec 2012 mass student strike & movement.

Having recently completed a seven stop all Ireland speaking tour, Vanessa Gauthier Vela answers some questions on the nature of the 2012 Quebec student uprising. This interview is a longer version of the one that appeared in the print version of Irish Anarchist Review 8. Audio from Vanessa's talks in Ireland will also be available soon.

1. Can you briefly summarise the struggle of 2012 for our readers?

In March 2011, the Liberal government of Quebec announced an increase in tuition fees of $ 1,625 over a period of 5 years starting in the fall of 2012. Ultimately, this increase would have nearly doubled tuition fees. At that time, the radical part of the student movement, organized under a national student union called ASSE, was already mobilizing to trigger, in the winter of 2012, a major campaign of general strike in order to resist the tuition hike.

The unlimited general strike officially started on February 13, 2012 when the first student unions voted the strike in their local general assembly. At the peak, we reached more than 300,000 students on strike, that is to say, three-quarters of all students in Quebec. By “unlimited general strike” Quebec student's movement meant a complete cessation of educational activities until the general assemblies would decide otherwise. No student who was part of a student union on strike had any classes to go attend. This not only put a great deal of pressure on the government, it also meant more free time for students to participate in actions and rallies.

Actions were multiple and included flash mob as civil disobedience. There was an escalation in the range of tactics used. As the strike got longer, the actions turned to be more radical and the people willing to take higher risks. At the same time were formed autonomous initiatives which helped to the organization of the strike. The food-committee is a good example; it was organized by students and was completely autonomous of national structure or local unions. Thanks to the people who got involved there we always had enough to feed there the strikers even during dangerous or long actions.

The plan was supposed to be simple: keep the pressure on the government first of all by keeping universities and colleges on strike empty and next by doing actions of disruption and demonstrations everywhere else. This had to be accomplished while resisting police repression. If we could hold on long enough, we knew that the government would be willing to negotiate. At least, that’s what previous general strikes in the history of Quebec student movement had shown.

We had not anticipated the importance of injunctions in the process of judiciary repression. A number of students against the strike, including some associated with the Liberal Party, went to court to force school administrators to do everything in their power to allow them to attend their classes. Some administrators interpreted these injunctions as a reason to call the police on campuses, fuelling a moment of violent clashes between strikers and police.

When negotiations were finally contemplated, the offer made by the government was perceived as an insult by the student movement. A spontaneous evening rally ensued, followed by demonstrations every evening for more than three months.

There were attempts to establish ties with other social struggles. The student movement enthusiastically joined the resistance of First Nations and environmental groups against the Plan Nord, a governmental plan to exploit the natural resources of the North, and in the context of Earth Day's rally. Connections have also been attempted with worker’s organizations by participating in their actions and inviting them to ours. However, even if workers unions have shown signs of solidarity by making donations or publicizing our actions, this connection was more difficult.

At the end of April, further negotiations with the government were announced, but they failed once again. The student unions on strike rejected the offer, and from there, some of them started to vote for an indeterminate strike "until the withdrawal of the hike."

In May, realizing that its intransigence and violence did not succeed in breaking the students, the government voted a special law, Bill 78. Spontaneous demos became illegal and organizations or individuals who participated or organized were subject to heavy fines. Also, the semester was suspended until the end of the summer, making strike votes non- effective since there were no classes anyway. Suddenly, we were strikers on lock out.

This law created a legitimacy problem for the government. Even people against the student strike wanted to denounce the anti-democratic law. It created what we called “les manifs de casseroles” or “pots and pans protests”. People from different neighbourhoods left their homes at 8PM and joined in the streets to protest loudly. The Metropolitan area and several towns saw joyful chaotic demos happening every evening. One of the positive long-lasting outcomes of the strike which emerged at that time was the autonomous neighbourhoods assemblies. They started with neighbours protesting with pots and pans and became spaces for people in the same neighbourhoods to organize themselves around political issues.

Meanwhile, the official suspension of the semester imposed a break in the struggle. Long months of constant struggle and repression were starting to fall heavily on people. With summer months, large portions of students had to start thinking about summer jobs. The strike was crumbling.

In August, the Liberal government called an election. From that moment on, the student movement broke up. On one side, students wanted to put energy into the election of a new government to address the issue of the tuition hike. On the other side, some believe that the strike should go on regardless of the campaign in order to put pressure on the new government whatever the outcome of the election. At the end of summer, the strike votes were not passing anymore in general assemblies. Some local unions resisted until the elections, but it was obviously the end of the unlimited general strike of 2012.

On September 19th, the new government, formed by the Parti Québecois, officially abolished the tuition hike by decree and repealed the Bill 78. Nevertheless, at the end of the strike, many of us stayed with a bitter taste in mouth. Not only because the electoral game made us lose control of our own movement, but also because the new government imposed on us an increase of 3 % every year. This last increase has not limitation in the time.

2. In the beginning, how did the student movement engage with the rest of the student population on the fee increase issue and get them to take action when the issue first arose? How did the student movement get other students to become aware of the issues and radicalise them?

The plan had already proved itself in past strikes. It had to mobilize as many people as possible on the topic of unlimited general strike not only with a massive information campaign, but also by involving students in decision-making about the struggle. At the same time, and as early as 2010, we had to engage the movement in an escalation of tactics that should bring, in winter 2012, the unlimited general strike as the only possible action against the hike.

"In 2010 and 2011, we focused on smaller-scale protests, training camps and other events with the objective of involving as many students as possible in their student union and in the committees formed around ASSE. By the end of 2011, not only were ASSE’s commitees packed, but cores of activists had gathered around many student unions. In September 2011, we launched a massive information campaign on campuses under the slogan “Stop the hike”4. All kinds of material was put out during that period: flyers, leaflets, posters, a website, video clips, research papers, etc. The goal was to get as much of this material into the hands of students as possible and get them thinking and talking about the upcoming tuition hike." (studentstrike.net)

The keywords were information and participation. In fact, the more people are actively involved in decision making and in the development of the action plan, the more they feel responsible and are ready to be radicalized. Thus, increasing the number of people mobilized and ready to act is far more important than the multiplication of conferences and articles on the subject, even if one does not go without the other.

3. Was there already a student movement in the Universities? Or was it born when the tuition fees were increased?

Quebec has a long tradition of student activism dating from the 60s and the structure of student organizations are recognized by law since the 80s. Before the strike of 2012 Quebec experienced major student strikes in 1968, 1974, 1986, 1990 and 2005.

4. What does an increase in student debt mean for ordinary students?

For a student who already has to work to study, an increase of his/her debt of study means first of all paying more interests to banks. It can cause financial difficulties at the end of the studies and delay some life projects as starting a family. It can also bring some students to neglect their studies or dropping out even without having obtained their degree. Also, for the marginalized groups as women or people of colour it also means to take longer to pay off their debts that a white man with the same degree.

5. Education can become an issue for everyone in society. How did activists engage with and mobilise other groups in society to involve them in the student struggle? Did students practice solidarity with these other groups?

At the 2012 strike we can make the criticism, along with the congratulations, to having the effect of uniting most of the left activists. From the moment the student movement was organized and positioned itself as an active actor in a social crisis of great scale, and that the government continued to refuse to negotiate with it, all social movements mobilized themselves in solidarity, and individuals who composed them were part of them

A lot of different people were involved in the strike others as being part of an organized group. We have seen unionists, anarchists, communists, feminists, anticolonialists, members of community groups and other groups being part of the movement and participate at actions and demos organized by students.

The strike was a space where a majority of activists channeled their energy towards the student movement. It helped to keep the strike very lively, but unfortunately it also led to the monopolization by the student movement, and sometimes in spite of itself, of all other issues, such as anti-colonial struggles and feminist struggles. But this space also helped building solidarities between groups. And if sometimes it was easy to go through the experiences of these to create these ties it was much more difficult to forge solidarity with structurally rigid groups such as unions workers.

6. Can you briefly describe CLASSE and its structure? How did the different groups communicate with each other effectively?

The CLASSE was a coalition of local student unions at the time of 2012 strike. It existed because the ASSÉ, one of three national student union, opened its structures to make possible for the local unions that weren't members of ASSÉ to be part of a national organization for the time of the strike. The ASSÉ is recognized as the most radical association. It promotes free education and acts on behalf of its values of direct democracy and syndicalism. It does not hesitate to take a stand on issues that go beyond education and encourages participation in decision making. It aims to be democratic and transparent.

The legitimacy and the accountability of the structure pass through the local general assemblies. In local general assemblies every member can make proposals and every member has a vote. Proposals can have local or national effects. They could be about principles, actions or in support with other struggles. When the objective of the proposal is to have a national effect, the delegation of the union that voted it in first place has to bring it to the congress as it could be discussed with all the other delegation members of the national structure.

The congress is the tool that allows the communication and decision-making at a national level. Usually the ASSÉ makes 2 congresses every year but for the needs of the strike it had to do organize congress every week. Delegates are not representatives of theirs union’s membership, neither were they sent in to express their personal views. The delegate's role is to bring up and defend the positions of their union’s own general assembly. As a result, only motions which have the support of a majority of local general assemblies can pass.

A congress is a perfect time not only to inform other unions on what's happening in ours, but the discussions that happen there are also useful to the radicalization and politicization of unions.

7. What was the specific importance of feminist organising in preparation for the struggle?

Minimal. Feminist made a place for themselves during the strike but they were not invited as feminists in the preparation of the strike. In fact, there were so many conflicts between the national team and the feminists in the ASSÉ that the whole women’s committee resigned a little before the strike.

8. Were there any issues around sexism or racism to deal with during the struggle?

Yes. First of all the dynamics between the former “comité-femmes” (women-committee) of the ASSÉ and the national team at the beginning of the strike did set the tone for the feminists who found that throughout the strike women’s issues were put at the bottom of the list. There was a paradoxical relation of cooperation and criticism between the feminists on strike and the rest of student movement. Feminists organized themselves in autonomous ways to explain why the hike was sexist. They produced papers, leaflets, and workshops on the topic of women and education, but also on the place of the women in the strike. Indeed, it did not take time to realize that the dynamics of the strike produced the same old reflexes as in any sphere of life. Men are usually more visible and make more valued tasks, whereas the women usually do invisible and little valued tasks. Throughout the strike, the feminists criticized these paternalistic reflexes in the movement by imposing critics as much as proposing solutions.

Throughout the strike, the feminists criticized these paternalistic reflexes in the movement and proposed many solutions to those issues.

The antiracism and the anticolonialism had much less space. In the CLASSE congresses it was difficult to bring anticolonialist proposals or proposals about foreign students. It demonstrated that the majority of the student population in Quebec are white and French-speaking. Issues affecting people of color as well as english speakers were pushed aside

9. Were there any tensions within CLASSE or the student movement?

The students' protest movement of 2012, as any punctual political alliance, was full of tensions between various groups or tendencies. A lot of people or groups would never have agreed to collaborate together in another situation. For example there is an historic distance and distrust between ASSÉ and two other national federations (FEUQ, FECQ). Some local union members of ASSÉ even have mandates of distrust or destruction of these federations.

The strike also raised the tension between people who understood their struggle as a fight against the government and the others who thought about it like an opportunity to convince “the public opinion" with pacific ways. Strangely, those who wanted to convince the public opinion always were the quickest to strike violently people who were smashing or tagging buildings and windows.

The space of the strike was full of tensions. Whether it was between moderates and radicals, between university students and college students, or between the metropolitan region and more distant regions, people were not always affected by the same issues and did not see the modalities of the alliance in the same way.

10. What tactics did the State, the media and the police use to try and defeat the students? Were any of their tactics particularly successful?

First of all, there was a constant struggle between the students' protest movement and the State, the bourgeois media, and the police, about the question of legitimacy. At the very beginning, the State tried to minimize our strike by using the word boycott and with the complicity of bourgeois media it tried to isolate completely the movement. They created a separation between bad-students-who-don’t-even-pay-taxes and good-citizens-who-pay-taxes-and-don’t-block-streets. The bourgeois media were firm opponents by the way they always minimized our actions and our rallies. On the other hand, pretexting to present both sides, every time they could interview a student against the strike they always put him under the spot and present him as a victim.

At some point bourgeois media became police informers. It was impossible to be part of the strike actions without our image was being taken by their cameras. Some students had the bad surprise to see their names in newspapers beside an action of civil disobedience where they weren’t even there. Of course, medias never apologize themselves for this kind of mistakes and were always complaining about us making their job of “inform the public” harder.

The physical brutality of the State against the students' movement and the judicial repression are certainly the tactics which had the most impacts on the students. While students were hit, lost eyes, got broken bones, were searched without mandate and imprisoned without being under arrest, the government, the bourgeois media, and the police, presented this violence as being the same thing as broken windows and graffiti. The sad thing is that a big part of the public opinion has never made the difference.

The injunctions were also difficult. These injunctions forced the direction of establishments to make everything in their power to allow classes to be given to those requesting the injunctions. It took all the courage of the students to block their institutions against the police which had been called to break their lines.

11. Has the struggle left a lasting impression on social movements in Quebec?

The strike of 2012 is the most impressive demonstration that a social movement left in Quebec since several years. In spite of a finale which leaves a bitter taste to several, it is undeniable that gains were made for the continuation of the socials movements.

First of all it shown that a punctual alliance on precise subjects could be large-scale, even when the various actors never usually work together. Activists' networks were established, spread, or solidified. There was a transmission of knowledge as regards the resistance at the repression of the State, and people generally became more radical. In the same way, groups decided to get organized in solidarity with people who had to wipe economic consequences of a long strike by food aid. For several groups, which take place in the range of services to the population, that was a moment of extreme politicization of which it is difficult to move back from. This politicization created new ties. One of the gains of the strike are the autonomous assemblies of districts that bring together neighbours who want to get organized politically and that did not exist before the strike.

It is also interesting to notice that in the general population a certain opening was made on principles which were little or not known before. For example, that at the end of the strike the principle of direct democracy is known by the public and that the bourgeois media speak about it are definitively gains. Of course the general population did not adopt these principles, but at least they were known, and we had given the proof that it was possible to work direct democracy in large-scale.

WORDS: Brian interviewing Vanessa Gauthier Vela

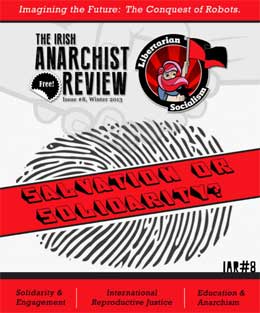

This article is from Irish Anarchist Review no 8 Autumn 2013